Some thoughts on the universalist and particularist philosophies of the Haggadah, from a paper I wrote last year. You can read the entire paper here, with its comparative study of three different Haggadot (Orthodox, Reform and Israeli).

While Jewish communities and individual Jews have long understood themselves in context of their place in the wider societies in which they have lived (the Talmud recounts, for example, a number of rules regarding how Jews should conduct themselves while under Roman rule), for most of its history Judaism has been a largely particularistic tradition, chiefly concerned with its own ongoing narrative and how Jews should behave qua Jews. As much as the Talmud understands Judaism to exist within a larger universe, it also establishes a hierarchy of values vis à vis internal Jewish responsibility:

A member of one’s household takes precedence over everyone else. The poor of one’s household take precedence over the poor of one’s city. And the poor of one’s own city take precedence over the poor of other cities. [1]

Rabbi David Ellenson comments that this Talmudic passage “bespeaks the primacy our tradition assigns the Jewish covenantal community in the Jewish hierarchy of values.” [2]

It was not until modernity that consciousnesses emerged within Judaism seeking to understand how Jews should behave and understand their heritage with a more universalistic outlook. Of particular note is how these new traditions played themselves out literarily, as Jewish philosophers and religious leaders attempted to articulate a new Jewish religious identity that wasn’t primarily inward-looking. Leopold Zunz – founder of the Wissenschaft des Judentums – argued that this philosophical character of Jewish literature can only be described paradoxically: simultaneously concerned with Jewish identity and Jewish otherness; of “particularism and universalism.” [3]

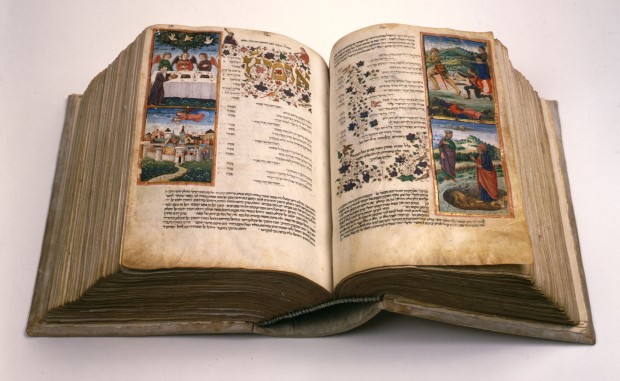

There is no text that straddles the boundary between particularism and universalism more acutely than the Pesach Haggadah’s retelling of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks posits that “the story of Pesach is intensely particularistic… yet no story has had greater impact on the political development of the West… [it] has been the West’s most influential source-book of liberty.” [4]

Andreas Gotzman and Christian Wiese point to the inevitability of this tension in arguing that it is necessary for a style of literature that simultaneously reflects on its own particularities, as well as its historical and cultural relationship with surrounding peoples.” [5]

Rabbi Jonathan Omer-Man, in his commentary on the Haggadah, notes that it is sometimes viewed as telling the story of the birth of a specific nation and people, while at other times, viewed as a “universalistic political statement, an affirmation that tyranny will be overcome in all places and at all times.” [6] In this textual interplay, the Haggadah makes use of biblical themes highly amenable to universalistic interpretations: freedom, liberty, justice, equality, and responsibility.

That said, while individual Haggadot are free to interpret and express these themes in their own universalistic ways, the Haggadah’s traditional paradigm remains largely particularistic to a specifically Jewish narrative.

The Haggadah’s role in the textual debate between Jewish universalism and particularism should not be understated. Thanks to the ease of modern publishing, one can find a plethora of Haggadot that emphasize and de-emphasize these ideological poles. To be sure, in 2014, Israeli journalist Mira Sucharov penned an article in Ha’aretz prior to Pesach asking Israelis the pointed question: “Are you a particularist Jew or a universalist one?” [7]

Each Haggadah – in dialogue with its own sitz im leben – puts forth a different paradigm of the Exodus narrative, applying varying degrees of particularism and universalism.

Go ahead and read the rest of the paper here…

[1] BT Baba Metzia 71a

[2] Ellenson, David. Universalism and Particularism: Jewish Teachings on Jewish Obligation. Jewish Philanthropy, April, 2014.

[3] Gotzman, Andreas & Wiese, Christian. Modern Judaism and Historical Consciousness: Identities, Encounters, Perspectives. Brill, 2007. Pg. 301

[4] Sacks, Jonathan. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’s Haggadah. Continuum International, 2006. Pg. 59

[5] Gotzman & Wiese, 301

[6] Omer-Man, Jonathan. Commentary on the Haggadah. in Conservative Judaism. Vol. XLII, no. 2

[7] Sucharov, Mira. What does your Passover seder say about you? Haaretz: April 7, 2014.